Doctors in Dialogue

Developing a Disaster Response Model with Dr. Grant Brenner and Dr. Jack Drescher

Welcome to the inaugural issue of “Doctors in Dialogue” from the Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry

In each issue, GAP members will discuss the latest developments in psychiatry, explore ongoing committee projects, review cutting-edge research, and delve into a wide range of relevant topics within the field. Thank you for joining us, and enjoy the dialogue.

Developing a Disaster Response Model with Dr. Grant Brenner and Dr. Jack Drescher

Dr. Jack Drescher: How did the Committee on Disasters, Trauma, and Global Health come into being?

Dr. Grant Brenner: When I first joined GAP, the committee didn’t exist in its current form. The committee was started by Knight Aldrich and Frederick Stoddard, Jr. as Disasters and Terrorism, then continued under Craig Katz as Disasters and The World. That’s what it was called when I became co-chair with Kathy Clegg several years ago. As disasters were becoming more complex, the committee’s focus evolved, and most recently we updated our name to the Committee on Disasters, Trauma, and Global Health to address a more inclusive set of considerations, from micro to macro levels. This broader scope allowed us to address not just singular events like hurricanes or terrorist attacks but also the increasingly common phenomenon of overlapping and cyclical disasters.

In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, it became clear that existing models of disaster response—such as the SAMHSA linear model, which tracks phases of heroism, disillusionment, and recovery—while useful, would benefit from greater breadth given the growing incidence and scope of crises and disasters. The standard model assumes a single event with a straightforward recovery process. But we were witnessing multiple, concurrent disasters—COVID-19, wildfires, and economic downturns which add strain and impede resilience—all interacting in ways that made traditional frameworks obsolete.

This realization led to the creation of the Model for Adaptive Response to Complex Cyclical Diasters–MARCCD– which is designed to help communities, organizations, and policymakers better navigate overlapping crises by capturing all the relevant factors impacting disaster preparedness, response, and recovery.

Dr. Jack Drescher: You’ve discussed that traditional disaster models often focus on single events. Can you elaborate on the idea of an "overlapping disaster"?

Dr. Grant Brenner: Yes, the traditional models usually focus on one disaster at a time, typically a point disaster—a single event followed by a sequence of reactions. What we’ve developed is a cumulative trauma, overlapping disaster model. A good example of this was the pandemic happening at the same time as wildfires.

Dr. Jack Drescher: So, you’re referring to people experiencing both the pandemic and the wildfires simultaneously?

Dr. Grant Brenner: Exactly. For instance, imagine living in California during the pandemic. You start to quarantine, but then you’re forced to evacuate due to wildfires. You're moved into a shelter with others, but the usual quarantine measures no longer apply. That’s a scenario where two disasters overlap.

These events don’t follow the same timeline either. For example, wildfires typically have an acute phase lasting about a week or two, followed by a sub-acute and chronic phase. In contrast, an earthquake might occur within seconds but comes with ongoing aftershocks. Communities affected by recurring disasters—like earthquakes—often have a collective wisdom that helps them cope. But then, there’s a difference between a community with strong financial resources for recovery and one that is under-resourced. A wildfire can cause additional smaller-scale disasters, such as suicide or the loss of a key community leader, further complicating recovery efforts.

Dr. Jack Drescher: So, before your model, previous frameworks only considered single events happening one after another, without readily addressing multiple events occurring concurrently?

Dr. Grant Brenner: Yes. While some models considered aspects like community resources, we didn’t see a model that explicitly tracked multiple disasters at once. With the MARCCD model, we developed with GAP, Vibrant Emotional Health, where I am on the Board of Directors and advise Disaster Services, and a company then known as Decision Point, we can visualize several overlapping disasters—showing their different timelines, phases, and the competition for resources. For instance, during the California wildfires, political decisions led to water hastily being released from dams during the winter, which ended up flowing into the ocean. Meanwhile, farmers will need that water for their crops during the summer, several months later. We don’t yet know what the impact will be if there isn’t enough water when it is needed.

Dr. Jack Drescher: That’s something I didn’t know.

Dr. Grant Brenner: Yes, it was a controversial decision. It’s an example of how resources—like water—can be diverted, causing further challenges. With our model, you can track how resources are being strained and anticipate the needs of communities competing for them. You can look down the road, and exercise foresight and careful consideration. MARCCD makes this explicit so that depending on the phase of a disaster, you can look ahead to what stakeholders are likely to need, while also taking care of things in the present.

Dr. Jack Drescher: Could you walk us through the four phases of disaster response?

Dr. Grant Brenner: Sure. Our model divides disaster response into four phases: Anticipation, Impact, Adaptation, and Growth & Recovery. These phases overlap, and while they’re sometimes presented in a linear fashion, the reality is that they’re cyclical.

Anticipation is when you expect a disaster, like waiting for a storm or anticipating a pandemic wave. This phase can vary in certainty. Sometimes, you know a disaster is coming based on accurate predictions, as we did with the pandemic.

Impact occurs when the disaster hits. This phase can last from seconds, as with an earthquake, to weeks, like the impact of a pandemic wave.

Adaptation is ongoing and overlaps with the other phases. While adapting to the current disaster, you might also be preparing for the next one. For example, you may be adjusting to life after being displaced by a fire, while anticipating another fire season.

Growth & Recovery is a phase where post-traumatic growth becomes possible. Not all disaster models include the idea of growth after trauma, but we see it as an essential part of recovery, helping communities rebuild stronger. Post-traumatic growth isn’t always required, however. Many communities return to baseline, hopefully fully recovering.

Dr. Jack Drescher: And how do these models get used? Who benefits from them?

Dr. Grant Brenner: These models are used by disaster response teams, and both governmental and non-governmental agencies and leadership. They are used at community, corporate, family, and individual levels. With the MARCCD model, we focused on three key groups—survivors, community leaders, and first responders. These groups are often the most in need of information to prepare for future disasters, but the model is informative for politicians, policy-makers, funding groups, and other stakeholders.

Dr. Jack Drescher: So, it’s both about learning from past disasters and preparing for the future?

Dr. Grant Brenner: Yes, and it’s also about capturing lessons learned in a way that can be shared. Too often, after a disaster, people just move on without reflecting on what happened. This prevents the community from learning and applying knowledge to future events. Our model encourages people to document their experiences during recovery and adaptation, so they can reference them later.

Dr. Jack Drescher: Do people use this model to learn from past experiences, or is it mostly for future preparation?

Dr. Grant Brenner: Both. The idea is to apply the model during recovery, so people can assess what's working and what's not. That feedback loop is crucial for adaptation. By providing a cognitive framework, the model helps people think more clearly under stress about many different factors. Without a framework, it’s easy to lose track of mission-critical considerations and miss key opportunities.

Dr. Jack Drescher: What is FEMA? Who’s in charge of disaster response, and how do they manage the mental health aspects?

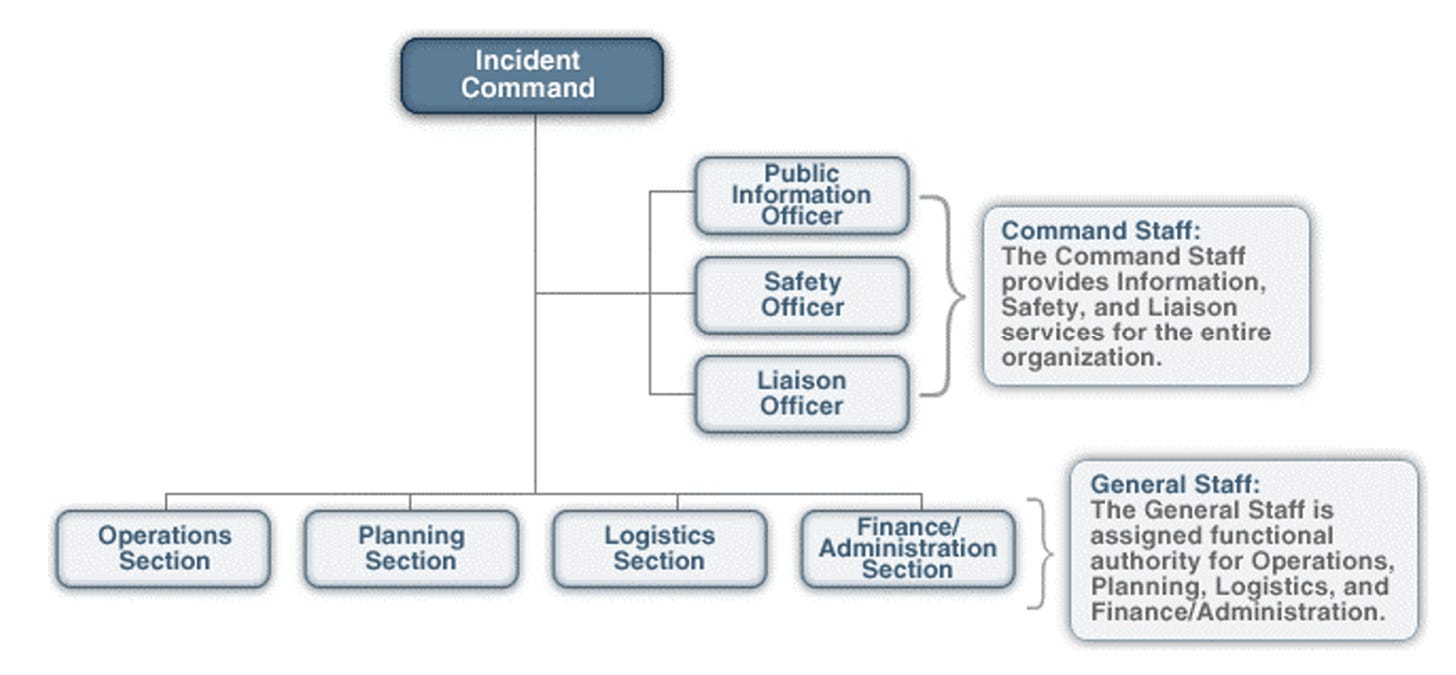

Dr. Grant Brenner: FEMA is the “Federal Emergency Management Agency”, the US governmental organization that oversees disaster response, and states also have their own disaster response systems, alongside a large array of groups that may be involved in disaster response, depending on what’s happening. Disaster response in the US is organized under the Incident Command System (ICS), a military-based structure. It’s a flexible framework that assigns leadership to various operational functions. However, mental health is often under-prioritized in disaster response. Emotional and psychological needs tend to get suppressed as people focus on immediate survival. But, long term, it’s vital to address these needs for proper recovery.

Source: https://www.usda.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ICS100.pdf

In the U.S., leadership during a disaster can be complex. For example, during the Afghan evacuation, the leadership was a mix of military and federal agencies. Our role was to integrate mental health support into these operations. We worked on training and offering services like psychological first aid and self-care skills for responders, consulting with leadership teams, performing needs assessment and triage, and consulting with displaced persons, staff, and contractors.

Dr. Jack Drescher: Can you tell me more about the challenges of managing such a large-scale disaster like the Afghan evacuation?

Dr. Grant Brenner: The coordination was difficult because military bases weren’t prepared to receive evacuees because of the suddenness of the effort. They did an amazing job under difficult circumstances, a testimony to leadership and team preparation and experience. The leadership had to be organized across multiple groups as a joint task force. Our role was to assess needs, provide direct care, and offer guidance to evacuees. We helped foster communication and bridge gaps, a unique role we can play as disaster psychiatrists, going beyond conventional mental health considerations to consult on systemic issues and help foster greater cohesion by resolving misunderstandings and making sometimes simple, but critical decisions–such as identifying how misunderstanding could lead to conflict, and how basic changes could resolve what had seemed to be a much bigger issue.

Dr. Jack Drescher: How large is the team involved in these kinds of operations?

Dr. Grant Brenner: It varies, but initially, it’s often just two people. It's critically important to have a “disaster buddy”. However, depending on the needs, teams can grow to three or four. Often, national and local philanthropic groups join the effort. The core task is to help coordinate and train these groups, and again work systemically to enable smoother functioning. We don't typically provide ongoing care but in some circumstances provide treatment and connect people with aftercare, depending on local resources. In Sri Lanka, for example, there weren't enough local clinicians, so we established a peer support program.

Dr. Jack Drescher: Is the leadership trained to understand your model, or do you adapt it as you go?

Dr. Grant Brenner: We’ve had a lot of interest in the MARCCD, and have presented in many venues with excellent feedback so far. Although it may seem overwhelming at first, once we walk people through it, they see its value. For example, the State of Missouri Department of Mental Health Office of Disaster Services found it compelling and supported our work so it could be offered to first responders and others. We developed short educational videos with them to explain different components, and once people saw them, they understood how to apply the model effectively. It was a unique opportunity to work with their forward-thinking team, one for which we are grateful.

Dr. Jack Drescher: Before we wrap up, is there anything you'd like to add?

Dr. Grant Brenner: One thing that stands out is the importance of having a coherent, shared framework like ours, especially in disaster response. There are a lot of organizations working in disaster response, but there’s no unified approach. Having a model that everyone can reference helps create a common language for all responders. Our committee at GAP recently published the second edition of Disaster Psychiatry: Readiness, Evaluation and Treatment, which includes a chapter on MARCCD, and every aspect of disaster mental health, from education and preparedness, technology and social media, leadership and organizational considerations, to prevention and response.

Dr. Jack Drescher: This has been really insightful, thank you.

Dr. Grant Brenner: Thanks, Jack. Appreciate the opportunity.

Video: Understanding the Cycle of Disaster (Part I)

Video: Understanding Stress and Recovery (Part II)

Video: Community Disaster Preparedness (Part III)

Disaster Psychiatry: Readiness, Evaluation and Treatment (2nd Ed.) https://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.appi.org/Products/Trauma-Violence-and-PTSD/Disaster-Psychiatry-Second-Edition&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1740712827167449&usg=AOvVaw0REwWs8zLErZ9aAyHWQrZ0

Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry, Committee on Disasters, Trauma and Global Health https://www.ourgap.org/committees/disasters-trauma-and-global-health

MARCCD Model for Adaptive Response to Complex Cyclical Disasters

https://marccd.info/

Vibrant Emotional Health, Crisis Emotional Care Team https://www.vibrant.org/what-we-do/advocacy-policy-education/crisis-emotional-care/